With this blog being hosted at and titled after my ham callsign, one might

expect there'd be at least a little radio-related content by this point.

I promise there's some coming, but for a stopgap enjoy this cover shot of a

pamphlet I found buried in the depths of a local antique mall:

I was too overwhelmed with the sensory overload that is shopping at an antique

mall to note down any interesting details, such as the date of publication.

It didn't have a price listed and it seemed like too much trouble to ask, which

is probably good since I really don't need such a volume in my possession.

Still, if there's one interesting takeaway, it's that Sylvania used to make

scopes?

A little over a year ago I decided to start carrying a multitool and,

not knowing anything about the product field, picked up a

Leatherman Wave+.

I've been more-or-less completely satisfied with it:

the scissors and wirecutters tend to runout a bit, but they're nonetheless

quite handy and the screwdriver is ingenious and by this point I can hardly

conceive of going back to life without it on my hip.

Now, this blog isn't, nor is meant to become a prepper/EDC lifestyle

accessory review site: there are plenty of those, they do a great job and

even go on to tell you what kind of hunter camo is in fashion this season to

wear at your wedding and stuff.

I digress.

I had an unpleasant experience attempting to service the above-mentioned

tool, and am calling that out as part of what I find to be a disturbing trend.

Last week I took my Wave+ fishing, and it ended up spending an hour or so

rolling around in bilgewater after falling out of my lap after I used it to

unset a hook and, well, you know how these things go.

This isn't the most respectful way to treat a tool, for sure, but it hardly

constitutes severe abuse near what you'd expect to damage a field tool like

this.

When I got back to shore I dried and oiled it but noticed it had picked up some

sediment internally that made the action a little gritty.

No problem, I'll just take it apart and clean it, as I've done with my

pocketknife any number of times.

Sound good?

Sounds good.

Except...

There's an old joke about the Soviet economy: "they pretend to pay us and we

pretend to work."

I've always thought similarly about security fasteners: the manufacturer

pretends they're sufficient to deter any attempt at meddling by the end-user,

while the end-user pretends not to attempt any field service since the

requisite tools are obviously impossible to obtain.

In point of fact, bit sets for these fasteners were one of the first things I

remember e-commerce being AWESOME at providing.

I ordered a set in about 2003

(from an online vendor that wasn't Amazon... how different things were).

Now, if ownership of a

security torx

bit set is the cost of entry to

attempt repair on a modern Leatherman tool, I'm basically OK with that.

Really I am.

It sets a baseline of earnestness and competence:

you've marketed the thing as a fine tool for the distinguishing craftsperson,

and you don't want your warranty department getting bogged down when JimBob

McHarborFreight ends up bending his the wrong way with help of a rusty

screwdriver and a pipe wrench.

Makes perfect sense.

And, in any case, I've got the right driver, right?

Except...

Yeah.

I have one.

Because anyone only ever needs one.

This is like how anyone only ever needs one can opener:

your can-opening needs, such as you ever encounter them, are perfectly met by

owning exactly one of the tool for the job, and no one is dumb enough to try

and design a can that needs two can openers applied simultaneously to work.

Yet there on the other side of the tool, that fastener mates another one with

the same drive type, necessetating a second identical driver.

This is literally the first time in my life I've ever had need of turning

more than one security fastener at the same time.

And it's all because some smartass engineer decided something like:

- these fasteners just look cooler

- (more cynically) we can drive repair revenue and product attrition through

by imposing arbitrary hurdles to owner maintenance

- (most cynically) we can use this to drive

sales of interchangeable bits

It turns out, (3) doesn't even make sense, since they don't even sell security

bits.

Way to hold the line there, leatherman, and keep those bits out the hands

of dangerous criminals.

You know, the types who might try to replace the battery in their own iPod or

turn off the seatbelt warning chime.

I honestly can't relate to the mindset of someone who, owning a tool company,

would intentionally design and build tools such that they can't be used to

work on themselves.

I suppose there's a possibility the reasoning aligned with another option:

- we really don't trust our customers to undertake repair of their own tools

Looking at third-party repair instructions,

there's some medium-complicated stuff in the stack: eccentric bushings and

friction washers, but nothing all that gnarly.

It can't any more complicated the spring-assist on my pocketknife, and that's

something I've torn down to clean enough times to confidently do it

blindfolded by this point.

Again, I'm basically satisfied with the tool in every other way, but this kind

of overt hostility toward what should be their key customer base is the sort

of thing that might have me looking elsewhere when it comes time to replace it.

Remember I'm not a review site, and I wouldn't recommend against buying this

tool for this reason alone.

Just, if you plan on undertaking a major service operation — like cleaning

some grit out of the mechanism — without sending it in for factory service,

remember to factor in the cost of an extra set of security bits to the TCO.

Then you get to be the only person on your block with both a shiny new

Leatherman tool and an otherwise completely redundant set of same.

Notes

My girlfriend teaches at a local college which has what they call an

"innovation and creativity center."

This is like a hackerspace for college students: they have a small laser

cutter, a bank of FDM machines, the standard stuff.

Its purpose is to give students access to resources for product design, rapid

fabrication, and other resources that students might employ throughout their

studies.

When COVID hit and they sent most of the students home, a small group of

faculty and remaining student workers started turning that equipment to

produce PPE for local hospitals and other communities in need.

So now they're making face shields, with a throughput of a few hundred units

a week.

They're making a couple different models from the many that exist now (the

fire department has stated a preference for one model, the hospitals like a

different one) but which are of the same general construction.

This consists of an FDM

or resin-cast frame, which holds an elastic piece in back for securement and

a piece of transparent PET sheet that comprises the shield.

The latter piece is laser-cut both for general shape and for holes to mate the

mounting studs projecting from the frame.

One problem they were having is that the PET sheet they've sourced comes

on giant rolls, and the material needs to be rough-cut down to fit on the

16x12" bed of the laser cutter.

The rolls are 48" wide, so this is easily enough cut down to either dimension,

but the difficulty comes in making a transverse cut across 48" of material

that's both reasonably square and also close to the 10" dimension required by

the design.

Some slop is forgivable, since each shield is cut entirely from the interior

of a piece and none of the rough cuts forms a finished edge.

But it was still proving awkward and cumbersome to measure and square this by

hand while managing the not-insignificant bulk of the roll itself.

This had become a bottleneck in their production process, so I decided

to build a fixture to help.

Design

Design requirements were pretty straightforward,

the fixture needed to provide three things:

- Some means of retaining the spool and allowing it to unreel in slightly more

elegant fashion than just flopping around on the work surface.

If this can help prevent its getting scratched, so much the better.

- Some form of stop, square to the axial dimension of the reel and against

which the working end of the material can be abutted and made fast.

- Some sort of guide, rigidly fixed at the desired distance of ten inches

from the stop, along which a cutting tool may be worked.

While this allowed a lot of flexibility in implementation, a challenge was the

timing.

This was late March, when Amazon was still quoting lead times of 4-6

weeks on "nonessential" items, hardware and home improvement stores were

basically closed and I myself was trying not to leave the house.

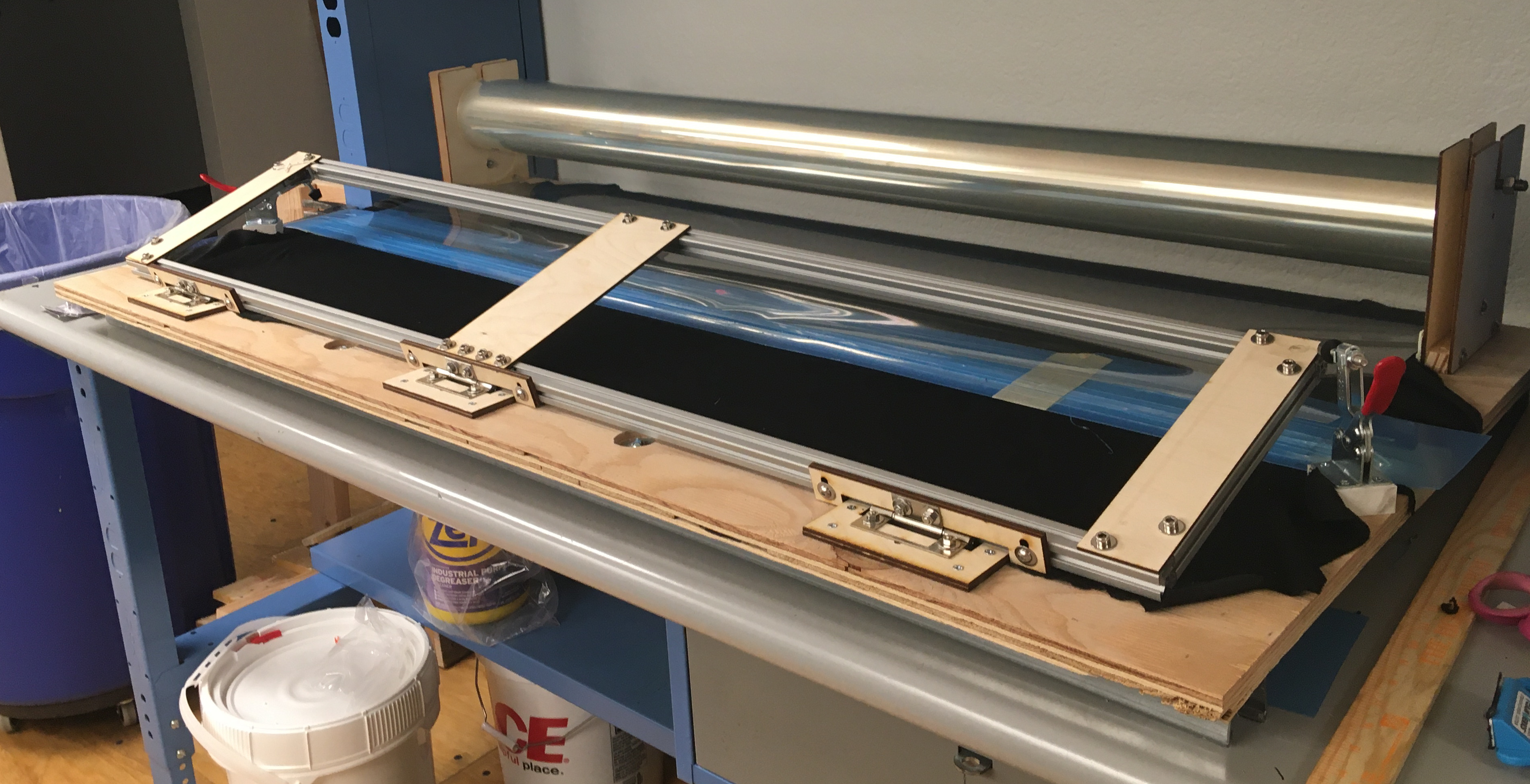

Here's what I made do with parts (mostly) on hand:

Assembly

The base is cut from some 3/4" subfloor plywood I had lying around.

This was plenty rigid but a little more warped than was reasonable for the

application, so I counterbored from the top and tied into a couple

lengths of steel strut-channel, which got it straightened enough.

With the limited materials I had to work with, this construction is going to

be a bit rough.

The reel is stood-off on plywood that the innovation center was kind enough to

laser for me, sandwiching some scrap 1x1 for rigidity and tie-in to the base.

This plywood is slotted to accommodate a length

of 3/8" all-thread, on which the ID of the spool sits.

The cutting guide is formed by the T-slot aluminum frame you see swung up

toward the image foreground.

This is corner-braced internally but also tied to more plates of laser-cut

plywood you see up top.

Edge-to-edge the frame is 10" wide,

and serves to measure this dimension in the direction toward the spool from

the plywood seen screwed into the base, to which the hinges are affixed

and which serves as the material stop.

When the frame swings down, it then defines a transverse line 10" from the

stop.

It can be toggle-clamped to hold the material in place, allowing the

operator both hands free to manage the cutting tool.

Lessons learned

Altogether this was a very edifying experience, for a couple of different

reasons.

From a systems perspective, this was a great object lesson in limiting

features to scope of project.

The engineer in me looks at requirement (1) above and

immediately starts picturing endcaps that mate the ID of the spool and ride

on sleeve bearings about the axial shaft such that the spool is balanced

around its CoG and spins freely and etc. etc.

That part of me is absolutely horrified at the thought of the spool just

rough-riding over a threaded rod like a roll of toilet paper.

Yet, it turns out, that works just fine.

Any attempt to build a more elaborate mechinism would have taken longer to

design and fabricate, imperiled ourselves of a re-roll if something didn't fit

or otherwise work, and been more likely to fail "in the field."

Similarly, I spent a lot of time thinking about requirement (3) and whether it

would be easiest to build a hot-wire cutter versus a straight, hook, or rotary

blade, what type of guide would best support same, what kind of clearance or

cut-out might be required to accomodate the tool in the bed, etc. etc. before

shelving all of that and just building a straight-edge.

I figured that, if a captive tool were that important, I'd hear about it.

In point of fact, the operators have made do with a manual knife just fine;

the straight-edge was all that was required.

There's a lot of talk in engineering circles about the perils of

overengineering,

YAGNI,

project scope, etc.

For all that talk, actually being able to define and hit targets is still

largely a matter of good judgement and experience and something even seasoned

engineers often fail at.

Being able to take something from concept to delivery and see that it

succesfully meets a need is a rare pleasure and one that keeps me in these

fields.

From a personal perspective, it was also very gratifying to be able to execute

with the limited parts and supplies I had on hand.

For years (at least when it comes to small parts like fasteners and toggle

clamps), my policy has been to buy 25-100% more than I need for the current

project "in case I need 'em for something else later."

This doesn't always feel like the right thing to do, what with the additional

clutter it brings and the alternative convenience of modern supply chains.

Most of my personal projects spend a long time in what we'll call the

"concept/pre-procurement phase."

Being forced by circumstance out of that and directly into execution with just

the stock I'd accumulated "in case I need it" was, again, a very gratifying

and singular experience.

Notes