Some notes on hygrometry

Every year about this time the weather starts getting interesting, and every year about this time I kick myself for having forgotten that the NWS SKYWARN spotter training classes are only offered in March and April. Luckily this year I wasn't doing much in April and our local NWS office did a FABULOUS job of presenting the training courses online, so I finally got my spotter ID. It's causing me to pay more attention to the weather and to meteorology as a science than I have since probably high school.

Aside from some intense thunderstorms this week (including a tornado warning for cloud rotation observed within city limits, which is VERY uncommon), it's also been uncharacteristically humid. Humidity is something we don't often pay much attention to around here, on account of its often never exceeding 30%. But I started reading up on the subject and learned a couple interesting things.

An instrument used to measure humidity is called a hygrometer, and they can be made to work by any of various phenomena. Mechanical dial-type gauges, such as may be found with a thermometer and barometer on a wall-mounted weather station, work by measuring the distension of a material or structure that expands and contracts in response to atmospheric humidity; human hair is one such material. The dielectric constant of air changes with humidity, so an electronic gauge can be made to work by measuring the time constant of a circuit built around an air-gap capacitor exposed to atmosphere. Alternatively, solid-state sensors exist which utilize a material whose resistance or other electrical properties change after absorbing moisture from the air. These are found in some consumer devices, as well as in the form of discrete components which can be purchased and integrated with hobbyist or industrial systems.

From left: Home weather station with dial-type hygrometer, barometer, and thermometer (via Wikimedia Commons, photo by Friedrich Haag); Low-cost digital thermometer and hygrometer; Hobbyist capacitative-type discrete humidity sensor from Sparkfun

A different, arguably more direct device works on the principle that evaporation occurs in inverse relationship to air humidity. Thus, by measuring the temperature differential between the ambient air and an thermometer evaporatively cooled in presence of same, the air humidity can be determined. Such a device is specially called a psychrometer.

These have two thermometers, one "dry bulb" which measures ambient air and one "wet bulb" which is moistened and reads cooler because of evaporation. Though I never built one, I remember seeing instructions in many childhood science books for how to do so. These were swung around over one's head to create enough airflow to sufficiently cool the wet bulb; precision instruments use a calibrated fan or blower to provide a known amount of airflow.

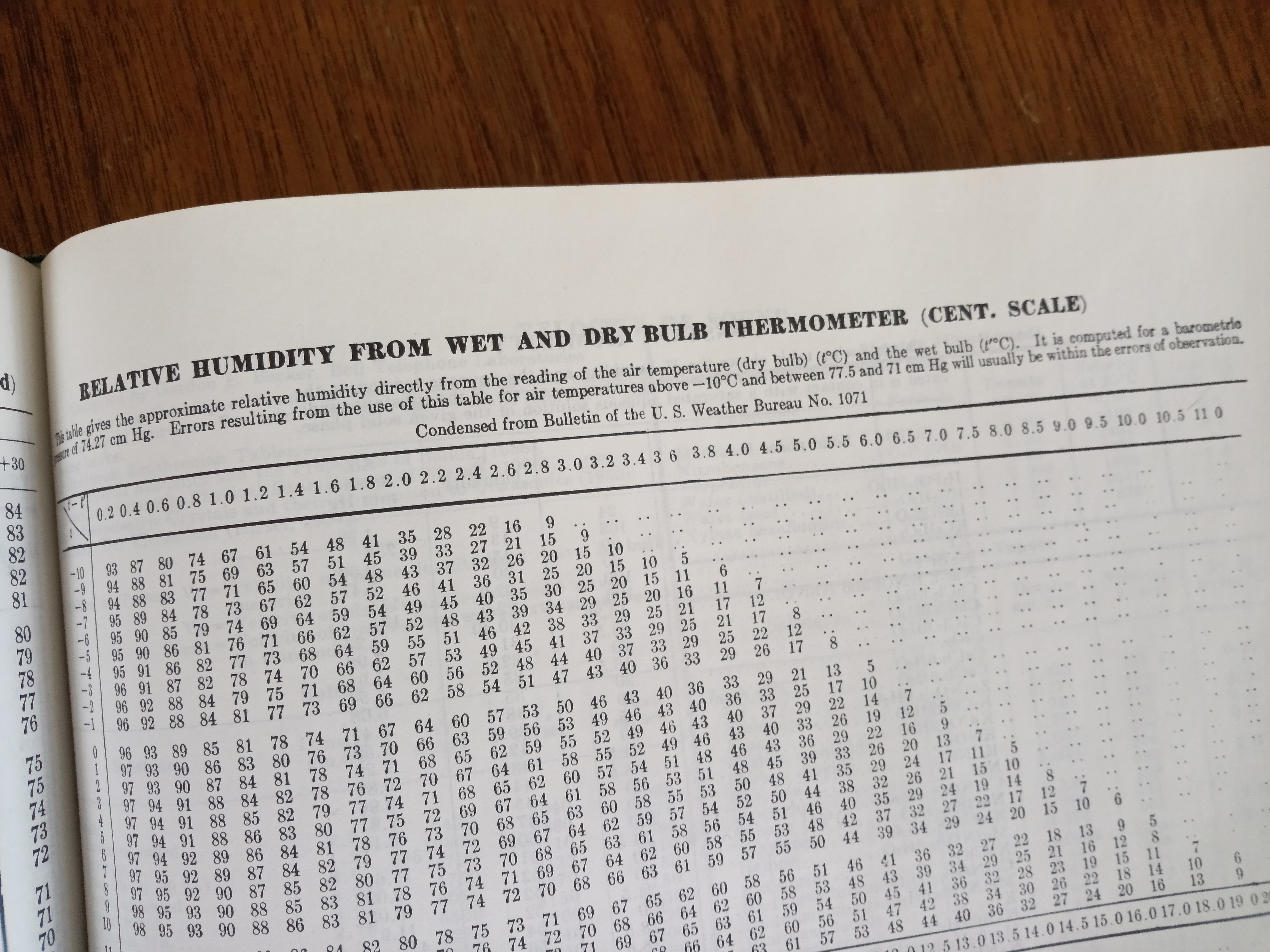

The relationship between humidity and the two temperature readings depends also on barometric pressure, and, if there's an analytic formula describing this relationship, I've never seen it. Instead all I've ever seen are tables, like the one shown below. In fact, I was given advice by a Physics instructor once to the effect of "you need a CRC manual from roughly every ten years or so, because they stop putting certain information in there. I was trying to find a wet-bulb hygrometer table the other day and I had to go back YEARS." Fortunately my 1967 edition has one (alongside other then-useful-now-WTF data like a table of haversines and the physical properties of whale oil).

Table of humidities as determined by psychrometer reading, from the CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 48th ed. (1967-68)

Sources of error for this instrument will be temperature effects from things other than the ambient air: radiative heating from the sun or other surroundings, or direct impingement of precipitation, for instance. You've probably seen the louvred enclosures at an airport (or, as my brother pointed out, at the end of the coincidentally-named movie Heat) that are used to mitigate these effects while allowing air more-or-less to freely circulate. I learned from the wikipedia article that these are called Stevenson screens and that their namesake inventor was the father of Robert Lewis of the name, author of Treasure Island (!)

A Stevenson screen

To conclude with one more interesting factoid from the wikipedia article:

One of the most precise types of wet-dry bulb psychrometer was invented in the late 19th century by Adolph Richard Aßmann (1845–1918); in English-language references the device is usually spelled "Assmann psychrometer."

Which, like, heh.